BLOG ARTICLE

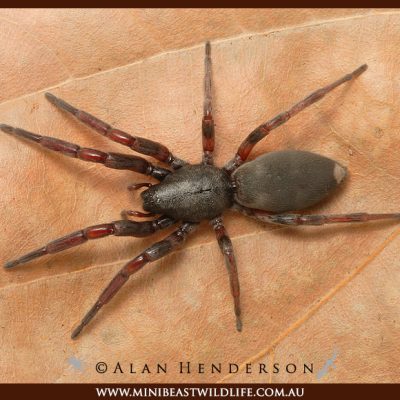

DO WHITE TAIL SPIDERS CAUSE NECROSIS? PUTTING SPIDER BITES TO THE TEST

You’re reclining on your couch in the late evening, watching something on TV and thinking about heading to bed. Out of the corner of your eye you see a flicker of movement. You look down to find a dark shape lurching across the floor in the shadows. You flick on the lights, and suddenly all thought of sleep evaporates. You’ve got them: the dreaded White-tailed Spiders. They have arrived.